For a few years now, I’ve been part of running physical game design workshops in various settings – usually with the aim of achieving something playable in a short time frame, before iterating on it quickly to see what we can build.

I’ve developed a short series of questions designed to get people on the same page at the start of a session, which I used at the AI Retreat in the context of building a board game. A couple of the other participants suggested I publish them so other people could use and adapt them – so here they are.

A quick note: these questions are designed for use in a small-group situation where you want to add constraints up front in order to minimise the time it takes to get something playable. They’re not doing the same thing as the double diamond design approach, which is all about going broad at the beginning of the process – you could look at this as a way to get right to the end of the first diamond very quickly, if you like. There are three main reasons for that:

- Practicality. These are best applied in situations where you don’t have a lot of time to diverge before you bring everything back together. They’re also good for other situations where there are significant constraints that you need to identify and agree up front.

- Playability. It’s immensely hard to playtest only part of a game – it needs to be mechanically complete enough to experience before you can really iterate on it. The aim here is to get to something, even if that something sucks, before pulling it apart again to make it better.

- Problem. Or, more specifically, the fact that there usually isn’t one. It’s rare for these kinds of game design workshops to start with a specific brief outside of the constraints themselves; when you’re making art you don’t usually start with a particular user problem. This gives you something to work with, to bound your creative process.

Physical game design toolkit

Pick the questions that you feel are most relevant to your current situation. Order them with the easiest ones to answer closer to the start – you’re aiming to get initial easy decisions banked. Consider setting a timer for each question; anything that takes more than five minutes to agree is probably an interesting place to explore creatively. Remember that none of these decisions are set in stone; at any point in development you can reopen them, and you’ll probably want to revisit most of them as you iterate on your game.

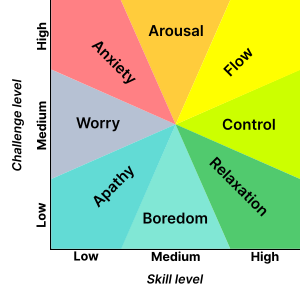

- How do you want your players to feel?

- Think both physical and emotional.

- Is there anything you explicitly don’t want them to feel?

- Who are your players?

- This might be a target audience demographic question, or a literal “my mate Jo” question.

- How should your players interact with each other?

- Some games – like Ticket to Ride – have limited player-to-player direct interaction; they’re mostly a race. Others – like Uno – are almost entirely players acting on players. Where do you want your game to sit on that spectrum?

- What genre of game is this?

- Board game, cards, physical, escape room, etc?

- Does the game have any specific physical affordances?

- Closely linked to q5 – is there any specific kit you need to use or not use?

- Think about accessibility issues that might arise from your decisions here.

- What skills do you want your players to use?

- Spatial skills, verbal, reasoning, logic, etc.

- Is your game centred on a puzzle to solve or a mechanic to experience?

- Is there a goal?

- If there is, do all players share the same goal?

- Is it possible to win the game?

- Can you beat each other, or be the best at the game?

- Is it a collaborative or competitive experience, or a blend?

- Is information public, private or a mix?

- Some games are perfect information games, where every player knows everything; poker is a mixed blend because every player has some public and some private knowledge.

- Do all players have the same rules?

- Is play synchronous or asynchronous?

- Is play enacted live or in turns?

- Note that you can play live asynchronously, and play turns simultaneously.

- Should players trust each other?

- How long does a single game take?

- Related to that, how long is a play (think about the shot clock in basketball) or a turn?

- What is the theme of the game – is there one?

- I would recommend trying to express the theme of a game through its mechanics, so this question may go hand in hand with q20.

- Does the game have a “world”? How much do you need to build up front, and how much is exposed through play?

- What is your core mechanic?

I’d like to thank William Cohen for his approach to bringing game design into the classroom, partners in crime and business Grant Howitt & Chris Taylor, and various Gamecamp crews for refining this approach. Also Andy Budd and Ben Sauer for suggesting I share this more widely.