The fundamental problem with this New Yorker piece on the psychology of first person shooters is that the writer doesn’t really understand game design. Now, I’m all in favour of mainstream journalists writing positive articles about video games, but despite its positivity this piece makes some fundamental misunderstandings about the psychology of gaming and the way game design works.

It’s clear that the writer is searching for reasons for the incredible success of first-person shooters, but it ends up in some extremely strange places. For one thing, FPS games aren’t the majority of the market; while the CoD and Halo franchises are very popular, so are World of Warcraft, GTA, Assassin’s Creed, and so on. Even the Wikipedia list of bestselling games the article tries to link to lists Gran Turismo, God of War, Uncharted and Little Big Planet alongside FPS games in the Playstation 3 category. The premise that FPS games are somehow special, justified by the sales figures, just doesn’t stand up.

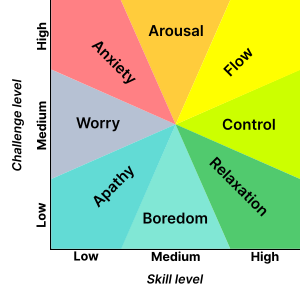

But the biggest problem is a fundamental misunderstanding of “flow”, and the mistaken belief that it’s somehow intrinsically linked to genre, rather than anything else:

What is it that has made this type of game such a success? It’s not simply the first-person perspective, the three-dimensionality, the violence, or the escape. These are features of many video games today. But the first-person shooter combines them in a distinct way: a virtual environment that maximizes a player’s potential to attain a state that the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow”—a condition of absolute presence and happiness.

Flow is not an intrinsic element of first-person games, nor of shooters. It’s not just presence and happiness: it’s concentration and absorption in a task, to the exclusion of all else. It is often an intrinsic element of good games – perhaps that explains why Kane & Lynch didn’t have the same effect as Half Life 2 – but it’s also an intrinsic element of lots of other experiences.

I get it from working out knotty Javascript problems in Twine, sometimes, from reading fiction, and from doing my day job during massive breaking news stories. I work like crazy to make sure that every player in our live games gets it at least once during the experience, too, because that’s often the clearest mark of a genuinely fantastic game. Whether it’s digital or physical, FPS or MMO, whatever your genre or even form conventions are.

And because of that, I’ve got to quibble with the assertion that “The more realistic the game becomes…the easier it is to lose your own identity in it.” The best flow situations I’ve built myself have come when people forget they’re playing, sure, but that isn’t linked to realism or to shooting or even to a first-person perspective and a sense of control. You can get it from dancing stupidly to disco music, from fighting in slow motion, from matching 3 jewels of the same colours over and over again, from Solitaire.

Realism and violence are not necessary for good game design. And good game design is not an adequate explanation for their popularity.